Examples of commonly changed estimates include bad-debt allowance, warranty liability, and depreciation. The amendments also clarify the relationship between accounting policies and accounting estimates by specifying that a company develops an accounting estimate to achieve the objective set out by an accounting policy. Now that we’ve defined accounting policy and accounting estimate, let’s step back and understand why the determination between a change in accounting policy versus a change in accounting estimate matters. The accounting treatment differs based on the type of change; therefore, it is critical to make the proper determination in the type of change. Back to the task at hand, we’re assuming a company had a long-term bonus arrangement for one of its employees, entitling them to $100 at the end of Year 4.

New Accounting Standards Upcoming Effective Dates for Public and Private Companies

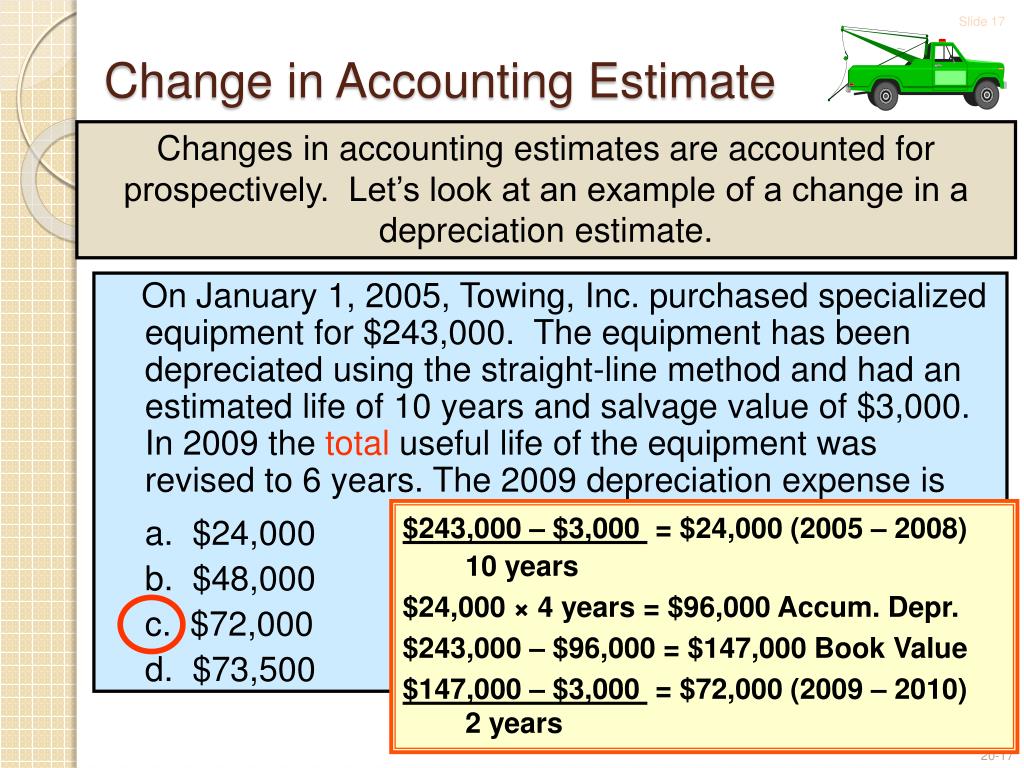

In fact, evaluating internal controls would be necessary even if the error doesn’t result in a restatement or adjustment to prior period financial statements. A change in accounting principle is the term used when a business selects between different generally accepted accounting principles or changes the method with which a principle is applied. Changes can occur within accounting frameworks for either generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), or international financial reporting standards (IFRS). Changes in the classification of financial statement line items in previously issued financial statements generally do not require restatements, unless the change represents the correction of an error (i.e., a misapplication of GAAP in the prior period). Reclassifications represent changes from one acceptable presentation under GAAP to another acceptable presentation. Entities must disclose the impact of a change in an accounting estimate on the income statement and any related per-share amounts of the current period when the change affects several future periods.

// Get the form field values

In this case, the business must disclose a description of that change in estimate whenever it presents the financial statements of the period of change. To muddy the waters a bit, there can be situations where a change in an accounting estimate results from a change in an accounting principle. This stems from either a change in estimate of future benefits of the asset, the pattern of consumption of these benefits, or the information available to the company about the benefits.

Little R Restatements

The approach taken can therefore affect both the reported results and trends between periods. Translating that to something a bit more palatable, the company reflects the change in the same period that the change in estimate occurred. Once again, you account for a change in estimate that you can’t separate from the effect of a change in accounting principle as a change in estimate. Likewise, suppose the change in estimate doesn’t have a material effect in the period of change but is reasonably certain to have a material impact in later periods.

IFRS update training

Playing off the previous example, let’s say a manufacturer discovers it classified certain selling expenses as cost of goods sold (COGS) instead of SG&A expenses in the income statement. ASC 250 presumes that once an accounting principle is adopted, a business should not change it for similar change in accounting principle inseparable from a change in estimate transactions. Further, the guidance explicitly states that a change qualifies as a change in accounting principle if a newly issued accounting standards update (ASU) requires it or, alternatively, if the entity can justify using an alternative accounting principle as preferable.

How Should a Change in Accounting Principles Be Recorded and Reported?

- If applicable, the reporting makes any offsetting adjustment to the opening balance of retained earnings for that period.

- Correcting the prior period financial statements through a Little r restatement is referred to as an “adjustment” or “revision” of prior period financial statements.

- That said, whenever the FASB issues a codification update, it typically includes transition guidance describing the applicable adoption methods.

- Neither business combinations accounted for by the acquisition method nor the consolidation of a variable interest entity are considered changes in the reporting entity.

An entity is required to disclose the nature of, and reason for, the change in accounting principle, including a discussion of why the new principle is preferable. The method of applying the change, the impact of the change to affected financial statement line items (including income from continuing operations and earning per share), and the cumulative effect to opening retained earnings (if applicable) must be disclosed. Correcting the prior period financial statements through a Little r restatement is referred to as an “adjustment” or “revision” of prior period financial statements.

Stay informed and proactive with guidance on critical tax considerations before year-end. Keep up-to-date on the latest insights and updates from the GAAP Dynamics’ team on all things accounting and auditing. We’ve established that determining the type of change is essential, so how do we do that?

If the change is determined to be a change in accounting policy, the change should be accounted for retrospectively. If the change in accounting policy is resulting from the initial application of an IFRS, the change in policy should be accounted for in accordance with the provisions in the IFRS. Changes as a result of errors are to be accounted for retrospectively (refer to IAS 8 for additional details). In many cases, a change in classification or presentation in the financials isn’t considered a change in accounting principle requiring a preferability assessment. This would include, for instance, a company that previously showed selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses together on the face of the income statement but now decides to separate selling from general and administrative expenses.

Once the company has quantified the error using the appropriate method, it then evaluates that error under the guidelines for quantitative materiality. Again, this step considers the materiality levels for the financial statements as a whole, which would include the impact on the subtotals and totals in the financial statements as well as the disclosures. To illustrate the difference between the iron curtain and rollover methods, let’s look at a simple example that ignores income tax impact and focuses solely on errors in the income statement and balance sheet. As a quick aside, remember that the company would also need to consider all implications to the other statements and any disclosures, like segment disclosures for public business entities. So how can management head some of the risks related to changes in accounting principles and estimates off at the pass?

If it is determined that a control deficiency exists, management should evaluate whether it represents a deficiency, significant deficiency, or material weakness. In doing so, management should consider the existence of mitigating controls and as highlighted in the SEC’s interpretive release,5 whether those controls operate at a level of precision that would prevent or detect a misstatement that could be material. “Big R Restatement” – An error is corrected through a “Big R restatement” (also referred to as re-issuance restatements) when the error is material to the prior period financial statements. A Big R restatement requires the entity to restate and reissue its previously issued financial statements to reflect the correction of the error in those financial statements. Correcting the prior period financial statements through a Big R restatement is referred to as a “restatement” of prior period financial statements. A critical element of analyzing whether a change should be accounted for as a change in estimate relates to the nature and timing of the information that is driving the change.